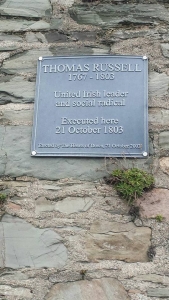

The Workers’ Party held a commemoration for Thomas Russell, co-founder of the United Irishmen, on Saturday 21st October at the Church of Ireland graveyard in Downpatrick. Below is the speech delivered by Gemma Weir, North Belfast branch.

The Ireland into which Thomas Russell was born in 1767 was in very many ways a different country from the country we live in today. Ireland (like the rest of the world) was a pre-industrial country in 1796. It was governed by aristocrats and the majority of people made their living on the land or in related trades. The formal political structures of eighteenth-century Ireland were based on religious background, and full membership of the political nation depended upon conformity to the Church of Ireland. Russell was raised an Anglican and was deeply religious throughout his life, but his radicalism would not allow him to accept the relative political privileges which his background allowed.

The Ireland into which Thomas Russell was born in 1767 was in very many ways a different country from the country we live in today. Ireland (like the rest of the world) was a pre-industrial country in 1796. It was governed by aristocrats and the majority of people made their living on the land or in related trades. The formal political structures of eighteenth-century Ireland were based on religious background, and full membership of the political nation depended upon conformity to the Church of Ireland. Russell was raised an Anglican and was deeply religious throughout his life, but his radicalism would not allow him to accept the relative political privileges which his background allowed.

Russell’s religious thinking tended towards a belief in the coming Armageddon of The Book of Revelations. Upon learning that he was to be executed, he asked for a stay of execution so that he could finish his study of the coming end times. Pre-figuring some ‘liberation theologians’, Russell’s Jesus was a radical, bringing comfort to the oppressed. “When will this social war cease?” Russell asked. “How my heart beats. Jesus wept… Were He to revisit this earth, where would He be found? Would it be at the Episcopal tables or with stall-fed theologians? He would be found in the cottier’s cabin. His hand would pour balm on the mangled body of the expiring husband; and His eyes would spread the consolation of heaven upon the wretchedness of the Irish peasantry.”

Rather than become an Anglican cleric as his father desired, Thomas Russell joined his brother Ambrose as a soldier, and later became a revolutionary activist, a prisoner and ultimately a martyr, dead at the age of 36. Rather than entering ‘good society’, Russell seemed to prefer the company of the poor. “I am much interested for this seemingly unfortunate young man Russell, wrote Martha McTier to her brother William Drennan in 1793. “He seems very poor, is very agreeable, very handsome and well informed, … His dress betrays poverty, and he associates with men every way below himself, on some of whom, I fear, he mostly lives…”

Russell was born at the cusp of the transition to new manufacturing processes in textiles, extraction and steam power that became known as the industrial revolution and his journals show his keen interest in scientific discoveries of his time. He was born into a world in which people were routinely bought and sold as slaves, and against which he protested by boycotting sugar. Mary Ann McCracken remembered that, as a young officer in Belfast, Russell had “abstained from the use of slave labour produce until slavery in the West Indies was abolished, and at the dinner parties to which he was so often invited and when confectionery was so much used he would not take anything with sugar in it.”

Thomas Russell was also born into a world of political revolutions. The French Revolution of 1789 encouraged radical movements in Scotland and England, and as far as Haiti where the slave revolt of 1791 led to that country’s independence from France. In Ireland revolutionary activism culminated in the 1798 rebellion which one historian describes as “little short of civil war”.

Having been a British soldier in India in the 1780s, Russell returned to Ireland and resumed his military career in 1790 as a junior officer in Belfast. The French Revolution in 1789 had been warmly greeted in Belfast as were its ideals of liberty, equality, and fraternity. In 1791 Bastille Day was enthusiastically commemorated in Belfast with parades involving local Volunteer companies, other celebratory activities and souvenir merchandise offered for sale and in October 1791, the Society of United Irishmen was formed in Belfast in Peggy Barclay’s tavern – a pub in an entry off High Street. Russell was an enthusiastic early member. “I confess”, Russell wrote, “ Pressure from Dublin Castle would later force the United Irish movement to become a clandestine organisation as the would-be revolutionaries sought to continue their slow progress towards challenging the status quo. In 1796 Russell was arrested and imprisoned without trial as a “state prisoner” in Dublin and later Scotland. missing out on participation in the 1798 rising as a result. What was the nature of Russell’s radicalism? His radical religiosity was a constant throughout his life, although it was tempered with the guilty pursuit of worldly pleasures. His political radicalism can be seen most clearly in his Letter to the People of Ireland, which was published in 1796, the year of his imprisonment. It is a historical document that can usefully be re-read in 2017. “Great pains”, Russell wrote, “have been taken to prevent the mass of mankind from interfering in political pursuits; force, and argument, and wits, and ridicule, and invective, have been tried by the governing party, and with such success, that any of the lower, or even middle rank of society who engage in politics, have been, and are, considered not only as ridiculous, but in some degree culpable; …. it became an indisputed maxim that the poor were not to concern themselves in what related to the government of the country in which they lived… Those insolent enslavers of the human race, who wish to fetter the mind as well as the body, exclaim to the poor, ‘mind your looms, and your spades and ploughs; have you not the means of subsistence; can you not earn your bread, and have wives and get children; and are you not protected so long as you keep quiet?’” It is here, in this radical egalitarianism, in this radical refusal of injustice that Thomas Russell speaks to us from the very different Ireland of 1796. Because the rulers of the world, still want to “to prevent the mass of mankind from interfering in political pursuits.” Referring to the rulers of Irish society, Russell asks us to, “look at their fruits in history, and see what terrible calamities the perfidy, ambition, avarice, and cruelty of these rulers have brought on mankind; look at the people who are said to make laws for this country; look at some of that race who inherit great fortunes without the skills or capacity of being useful; those fungus productions, who grow out of a diseased state of society, and destroy as well the vigour as the beauty of that which nourishes them. These are some of the wiser heads; these are the hands in which the people are to repose their lives and properties; for whose splendid debaucheries they must be taxed; and for whose convenience they must fetter even their thoughts.” Despite the development of industry and invention in the past two hundred years, the glaring injustices that inspired Russell to a revolutionary life persist in 2017. These injustices and the lives of revolutionaries such as Russell are our inspiration. At this graveside last year Lily Kerr spoke fondly of the similarities between Thomas Russell and our late friend and comrade, Des O’Hagan. Des O’Hagan was a source of inspiration to many if not all of us here today and a founder and driving force behind these annual events. He was, like Russell, a great voice against injustice and sectarianism on this island and around the world. We are honoured to remember him along with Thomas Russell here today. Unfortunately, this scathing judgement could be used to describe the political and economic rulers of Ireland in 2017 as much as those of 1796. The farcical politics of Northern Ireland played out by the sectarian parties do not blind us to tragic outcomes that the current economic system visits upon the majority. Meanwhile in the South, the Irish Times reports that in 2016 according to the annual Forbes ranking of global billionaires six Irish citizens are members of the billionaires’ club with a combined net worth of more than $30 billion (€27.6 billion), The richest Irish-born billionaire is include Digicel founder Denis O’Brien, whose fortune is estimated at $5.7 billion, while financier Dermot Desmond is estimated as being worth $1.9 billion. Other statistics show that the top 10% of households receives 24% of Ireland’s total disposable income while the bottom 10% of households only receives 3% The number of people officially living in poverty in Ireland has increased by more than 100,000 since the onset of the recession – meaning that 750,000 people in Ireland currently live in poverty including one in five children.

Unfortunately, this scathing judgement could be used to describe the political and economic rulers of Ireland in 2017 as much as those of 1796. The farcical politics of Northern Ireland played out by the sectarian parties do not blind us to tragic outcomes that the current economic system visits upon the majority. Meanwhile in the South, the Irish Times reports that in 2016 according to the annual Forbes ranking of global billionaires six Irish citizens are members of the billionaires’ club with a combined net worth of more than $30 billion (€27.6 billion), The richest Irish-born billionaire is include Digicel founder Denis O’Brien, whose fortune is estimated at $5.7 billion, while financier Dermot Desmond is estimated as being worth $1.9 billion. Other statistics show that the top 10% of households receives 24% of Ireland’s total disposable income while the bottom 10% of households only receives 3% The number of people officially living in poverty in Ireland has increased by more than 100,000 since the onset of the recession – meaning that 750,000 people in Ireland currently live in poverty including one in five children.